Class action plaintiffs suing the US government over a warrantless search of their safe deposit boxes housed at a now-defunct Beverly Hills company won an appeal Tuesday reviving their claims.

A Los Angeles federal judge had granted summary judgment in favor of the government, saying the search fell within the inventory exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement.

But the inventory search doctrine—which is typically applied in the context of routine searches of arrestees or impounded vehicles—didn’t apply to the dragnet investigative search of hundreds of safe deposit boxes, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit held.

One of the most important features of the doctrine is the existence of standardized instructions. But here, the government implemented supplemental instructions designed specifically for the raid.

Those extra instructions took the case outside of a standardized “inventory” procedure, the court said.

It also held that the district court abused its discretion in ruling that law enforcement didn’t exceed the scope of the warrant.

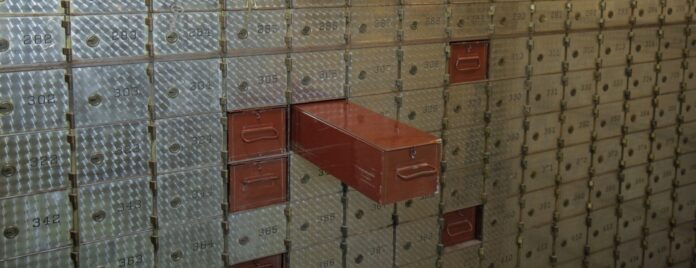

The FBI had obtained the warrants to search the premises of US Private Vaults, claiming the company “was aiding criminality and protecting criminals by operating a vault of anonymous safe-deposit boxes.”

In executing the warrants, agents purported to inventory the contents of the safe deposit boxes housed on the premises. But it failed to create much of an inventory, instead conducting something that looked more like a search for criminal wrongdoing, the plaintiffs claimed.

Before applying for the USPV warrant, the government had hatched plans to initiate civil forfeiture proceedings against all boxes that met a minimum monetary threshold of $5,000. At no point did it seek a seizure warrant for the box contents, nor a search warrant to see what was inside them, the plaintiffs said.

Its warrant application instead affirmatively stated that the search would “extend no further than necessary to determine ownership.”

It didn’t mention the property would be subjected to canine sniffs or that agents would be instructed to record observations that could be used in eventual forfeiture proceedings, the plaintiffs said.

Relief, Deterrence

The plaintiffs aren’t asking for any monetary relief. The lawsuit instead seeks an order directing the government to sequester or destroy all records, including photographs and video recordings, that it created during the course of the purported inventory search, so that they can no longer be used for investigative purposes. The plaintiffs’ property has already been returned, the court said.

Following oral argument, the government recognized that the panel was likely to side with the plaintiffs and moved to vacate and remand the district court’s judgment with instructions to grant the relief they seek. But the plaintiffs opposed any attempt to moot the appeal, saying the government’s “quasi-confession” underscored the need for a precedential opinion.

“If the government truly recognizes that it erred, then that underscores the seriousness of the constitutional violation,” plaintiffs counsel argued. “And if the government is trying to avoid a precedential decision, then that dramatically highlights the risk that the government will try to do this again.”

In a reply, the government acknowledged that it wanted to “avoid a published judicial opinion impugning the actions or good faith motivations of law enforcement” in what it called a “highly unusual case,” but said there was nothing “sinister or unfair” about agreeing to the plaintiffs’ demands.

An unnecessary published decision could have “unintended consequences” for very different cases, the government said.

Judge

Smith also wrote separately to say that he would have held that given the greater privacy interests and rights of third parties, that the inventory search doctrine doesn’t extend to searches of safe deposit boxes.

Institute for Justice and Vora Law Firm PC represented the plaintiffs.

The case is Snitko v. United States, 9th Cir., No. 22-56050, 1/23/24.